Starting the Linux Adventure - Preparing for Gentoo Installation

Greetings, young mages!

First of all, do not be intimidated by the amount of text in today's Chapter, but to turn an ordinary sorcerer into a true Witcher, one must acquire solid foundations, which is why at the beginning I will explain every spell and gesture in detail. Future meetings will not be as detailed in descriptions but more concise and focused on strategic spellcasting. To start your Linux adventure, follow these steps to prepare a bootable USB or CD for Gentoo Linux installation:

- Download the ISO image:

- If you want to perform the installation on a virtual machine or use a second computer (tablet, phone), download the Arch Linux ISO.

- If you want to install Gentoo on the same computer where you will be learning black magic, download a distribution with a graphical environment that will help you follow the instructions during installation.

- Requirements: For a direct installation on a computer (without a VM), you need a 4GB or larger USB drive.

- Visit gentoo.org, archlinux.org or NeonKDE

- Find the "Download" section and click the latest ISO image to download the file.

Attention!

What to choose?

Remember that experimenting with operating systems can result in complete data loss!

In Linux, you are the master of the underworld, so one careless typo and you can wipe your hard drives. There are also tools that can help you recover them, but we will get to that in the future, and now you need to install the system somewhere.

- Installation in a VM:

- 99% of you have a Windows computer, so the safest option is to use a virtual machine. Below I have shown you a brief description of how to run QEMU where you can experiment with spells, but you can use any virtualization system such as VirtualBox or VMWare, but this option is very slow because the computer has to handle two operating systems.

- If you have a second computer at your disposal where you are not afraid to experiment, this option is the best and most convenient.

In Linux, USB block devices are located in the /dev/ directory and named sd.. followed by sequential letters - sda, sdb, sdc, etc... As I hope you know, disks can be divided into partitions, but the physical device is the disk, not the partition. A partition is a logical device.

Partitions in Linux are numbered sequentially after the letter, for example:

/dev/sda1, /dev/sda2...

/dev/sdb1, /dev/sdb2... ..., /dev/sdb78

/dev/sdc

...

...

Graphically, it looks something like this:

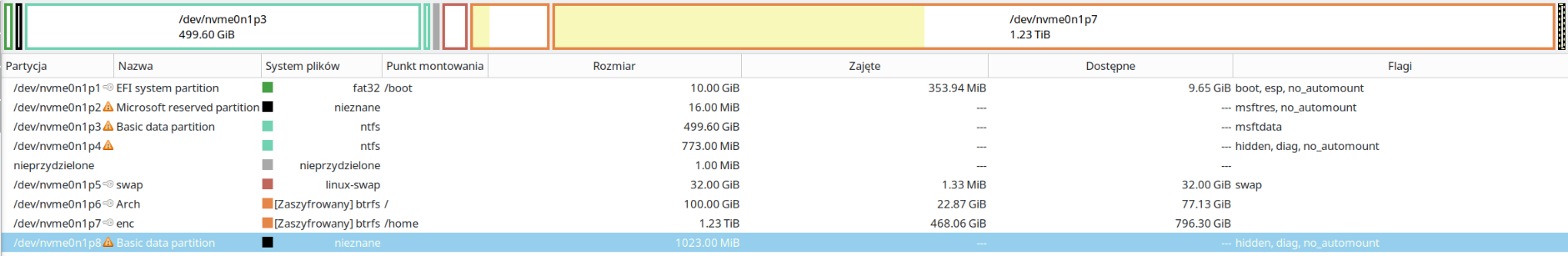

The difference is that my disk is not connected to a serial bus (SATA and SCSI disks) but to a PCIe bus, so the system names them differently, usually "nvme", and the naming convention is similar:

nvme0n1p1 - the first partition of the first disk connected to the first controller (numbering starts from 0)

nvme1n1p5 - the fifth partition of the first disk connected to the second controller.

The downloaded ISO image is an image of a device (some data carrier on which someone previously prepared a bootable system). Bootable, meaning one from which you can start the computer.

When you restore (write) the downloaded ISO image, you restore the device image to another device - your USB drive. Your USB drive likely has one partition, and the system detects it as /dev/sda1. But since you are restoring the image of the entire device, you restore it to the entire device /dev/sda, not to the partition /dev/sda1.

How to check the name of your USB drive?

The easiest way is to look in the /dev directory - this is the directory where all system device files are located. We will discuss the /dev directory and the system tree later, but now you need to check which letter your USB drive has been assigned.

Remove the USB drive from the computer and go to the /dev directory. Here we learn the first command "cd" - change directory, which allows us to navigate between directories, and from now on it will be familiar to you.cd /dev

The "ls" (list) spell displays the contents of a directory. This command (like most Linux commands) has parameters. You can see the list of parameters by typing ls --help. --help is a standard parameter, and if the program is not some punk invention written in a basement under a blanket, the --help parameter will work.ls -l sd*

Here we also need to pay attention to "-" and "--". Command parameters have short and long versions. For short versions, a single "minus" is used, for example, "ls -ar" means the same as "ls --all --reverse"

The "ls" spell will list the contents of the /dev directory.

The "-l" parameter will force a long output format, meaning it will format the command output as a list.

"sd*" will limit the result to file names starting with "sd", and the asterisk replaces all characters.

You can type all three versions of the command one by one to see the difference.

So, remove the USB drive from the port and type:

And see which devices are visible in your system. If you don't have any sd* devices, the command will display a message that there is no such file or directory.ls -l sd*

Then reinsert the USB drive and type the same command again. This time, a new device should appear, which is your USB drive, and this name must be provided as the "of" parameter of the "dd" command.

We will discuss the "dd" command itself later. - Create a bootable drive:

- On Windows: Use Rufus to create a bootable USB drive:

- Select the ISO file and your USB drive.

- Click Start and wait for the process to complete.

- On macOS/Linux: Use the

ddcommand in the terminal: - !!!! Attention. Linux is case-sensitive !!!

Now go to the directory where you downloaded the ISO:

or cd ~/Desktop - just go to the directory where you downloaded the ISO. Here are some more magical commands and gestures:cd ~/Downloads

This command shows the current directory you are in.pwd

Check how the tab key works in bash - it is a very helpful gesture. Commands work better with a wand, and the shell works better with the tab key. The tab key "completes" or lists (casts the "ls" spell), which significantly speeds up work. For example:TAB (press the tab key)

We will discuss what the above commands mean later, but now we need a runtime environment, so for now, just open the terminal (the black window of black magic), insert your USB drive into the computer (i.e., into the USB port ;)), find its name, and type in the terminal what is below.cd /home/tom/Downloads - we go to the "Downloads" directory in the home directory of the user "tom" ls - list the contents of the "Downloads" directory ==> here we see the list of items in Downloads and type the command: dd if=[TAB] - press the tab key, and after pressing [TAB] we will see the result of the ls command, then continue typing: dd if=ar[TAB] - press [TAB] again, and at this point, all files starting with "ar" will be displayed, and if there is only one, its name will be automatically inserted into the command line, and we will get something like this: dd if=archlinux-2025.02.01-x86_64.iso - now we can continue typing the command: dd if=archlinux-2025.02.01-x86_64.iso of=/dev/sdX bs=4M status=progress - Replace X in

/dev/sdXwith the name of your USB device, i.e., /dev/sda or /dev/sdb, c, d...

Be careful!

Make sure you select the correct device!sudo dd if="path and name of the downloaded ISO image" of=/dev/sdX bs=4M status=progress

- On Windows: Use Rufus to create a bootable USB drive:

- Boot from the drive:

- Restart your computer and enter the BIOS/UEFI (usually by pressing

F2, F9, F12,DelorEscduring startup). If you don't know, check online which key to press during startup to enter the BIOS. - On some computers, especially newer ones, you may need to disable "Secure boot" [SB]. SB in theory is a very good option that prevents unauthorized software from running on the computer. Unfortunately, in practice, thieving corporations - such as the one from Redmont, influence hardware manufacturers and use SB to block the ability to install other operating systems on computers. Fortunately, today you can still disable SB in the BIOS.

- Set USB or CD/DVD as the first boot device.

- Save changes and restart. The system will boot into the Gentoo or Arch Linux environment.

- If you are installing in a virtualized VM environment, create a 50GB disk, point the virtual machine to the downloaded ISO image as the CD drive, and start the VM. How to do this?

- Install QEMU (or another virtual machine) In the black magic window, cast the spells:

- Go to the home directorycd ~

- Create the OOS directory (or any other)mkdir OOS

- Enter the OOS directorycd OOS

You can also copy the downloaded ISO image to the same directory. In Windows, I assume you know how to do this. In Linux and Mac:qemu-img create -f qcow2 gentoo.img 50G

If you have created a hard disk image and downloaded the ISO image, you can start the environment to build your own black magic portal:mv ~/Downloads/image.iso ~/OOS/(enter the correct path to the downloads directory and the ISO file name)Linux:

qemu-system-x86_64 -m 4G -smp 4 -enable-kvm -cpu host -drive file=gentoo.img -cdrom archlinux.iso -boot order=d -nic user,model=virtio-net-pci,hostfwd=tcp::2222-:22 -display gtk,zoom-to-fit=on -vga virtio -usb -device usb-tablet -drive if=pflash,format=raw,readonly=on,file=/usr/share/OVMF/x64/OVMF_CODE.4m.fd -drive if=pflash,format=raw,file=/usr/share/OVMF/x64/OVMF_VARS.4m.fdWindows:

qemu-system-x86_64.exe -m 4G -smp 4 -cpu host -drive file=gentoo.img -cdrom archlinux.iso -boot order=d -nic user,model=virtio-net-pci,hostfwd=tcp::2222-:22 -display gtk,zoom-to-fit=on -vga virtio -usb -device usb-tablet -drive if=pflash,format=raw,readonly=on,file="C:\Program Files\qemu\share\edk2-x86_64-secure-code.fd" -drive if=pflash,format=raw,file="C:\Program Files\qemu\share\edk2-x86_64-vars.fd"

Explanation:qemu-system-x86_64: choose your CPU type. If your computer hardware is from Windows and is less than 15 years old, then 99% the option qemu-system-x86_64 is the right one for you. If you have older hardware with a 32-bit processor, choose qemu-system-i386. For older Macs with Intel processors, choose qemu-system-x86_64, for newer ones (with M2, M3, M4) choose qemu-system-aarch64 QEMU can emulate almost any available processor type, so choose the right one.

Command / Option Description Linux qemu-system-x86_64 Run QEMU in 64-bit mode. -m 4G Allocate 4GB of RAM. -smp 4 Set 4 CPU cores. -enable-kvm Use KVM for better performance. -cpu host Use the host's real CPU. -drive file=disk.img,format=qcow2,if=virtio Disk image `disk.img` in QCOW2 format with VirtIO interface. -cdrom system.iso ISO image `system.iso` as a CD-ROM drive. -boot order=d Boot first from CD-ROM. -nic user,model=virtio-net-pci,hostfwd=tcp::2222-:22 NAT network emulation with VirtIO driver, port forwarding 22 to 2222 localhost -display gtk,zoom-to-fit=on Run QEMU in a GTK window with automatic size adjustment. -vga virtio VirtIO graphics driver for better performance. -usb -device usb-tablet Improved mouse handling in the QEMU window. -drive if=pflash,format=raw,readonly=on,file=/usr/share/OVMF/x64/OVMF_CODE.4m.fd

-drive if=pflash,format=raw,file=/usr/share/OVMF/x64/OVMF_VARS.4m.fdUEFI BIOS firmware files Windows qemu-system-x86_64.exe Run QEMU in 64-bit mode on Windows. -m 4G Allocate 4GB of RAM. -smp 4 Set 4 CPU cores. -cpu qemu64 Use the emulated `qemu64` processor (better compatibility with Windows). -drive file=disk.img,format=qcow2,if=ide Disk image `disk.img` in QCOW2 format with IDE interface for better compatibility. -cdrom system.iso ISO image `system.iso` as a CD-ROM drive. -boot order=d Boot first from CD-ROM. -netdev user,id=net0,hostfwd=tcp::2222-:22 Create a network device in user mode, port forwarding 22 to 2222 localhost -device e1000,netdev=net0 Emulate an Intel e1000 network card. -display sdl Run QEMU in an SDL window (more compatible on Windows). -vga std Standard graphics driver for better compatibility. -usb -device usb-tablet Improved mouse handling in the QEMU window. -drive if=pflash,format=raw,readonly=on,file="C:\Program Files\qemu\share\edk2-x86_64-secure-code.fd"

-drive if=pflash,format=raw,file="C:\Program Files\qemu\share\edk2-x86_64-vars.fd"UEFI BIOS firmware files

Read more about QEMU - Restart your computer and enter the BIOS/UEFI (usually by pressing

With the bootable drive ready, you are prepared to dive into the world of Linux. Let the adventure begin!